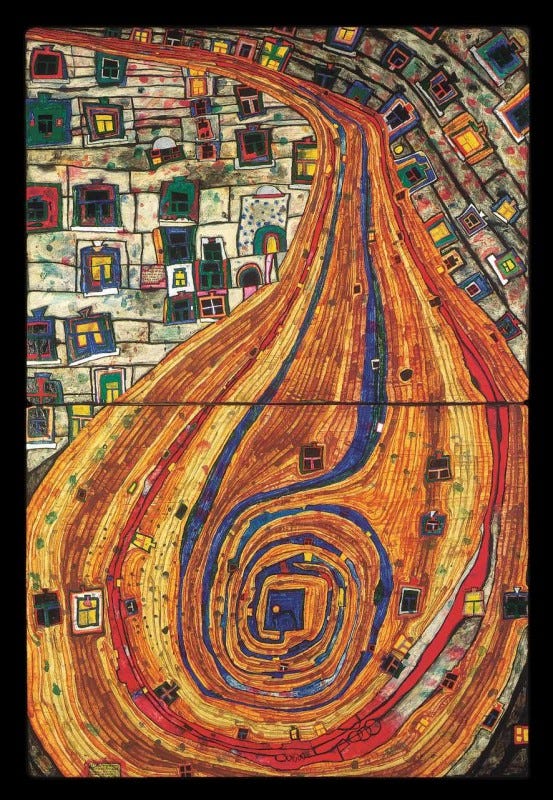

The Straight Line Leads to the Downfall of Our Civilization

Welcome to the World of Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Sometimes a seemingly insignificant incident can make a life-long impact. That pretty much sums up my relationship with the art of Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928 – 2000). Back in the Stone Age, as a college freshman, the walls of my room were covered with rock’n roll posters. Then I stumbled across a print of Hundertwasser’s work. His artwork stunned me. I had to hang the print in my bedroom so I could see it every morning when I woke up.

As a child of Eastern European immigrants, my creativity was supposed to be channeled into the sciences or engineering. Art was not a career option. But no matter how hard I tried to have a practical, conventional career, (I was a pre-med student) I couldn’t change my true self. I went on to get a PhD in Policy Analysis when I realized I’d never be happy until I fed that creative bug that kept gnawing at me. Art wasn’t a career choice, it was a reality.

By this time the Hundertwasser print was long gone. Like most students, I moved around a lot and things just disappeared into the black hole of college life. After grad school I took figure drawing classes and began to paint, experimenting with various techniques and mediums in search of my own visual style. Before long Hundertwasser reappeared. Not on my walls, but in my work.

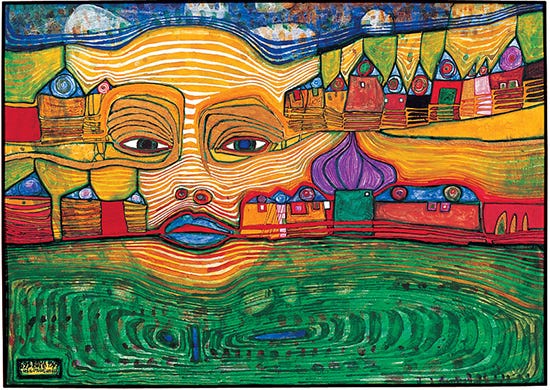

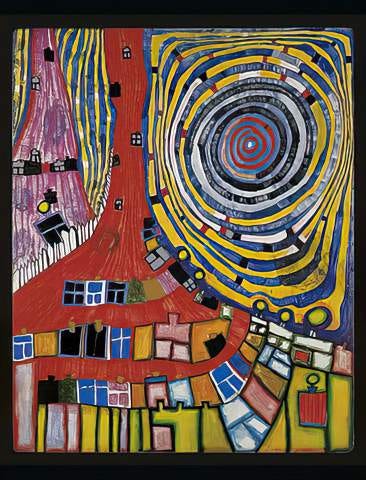

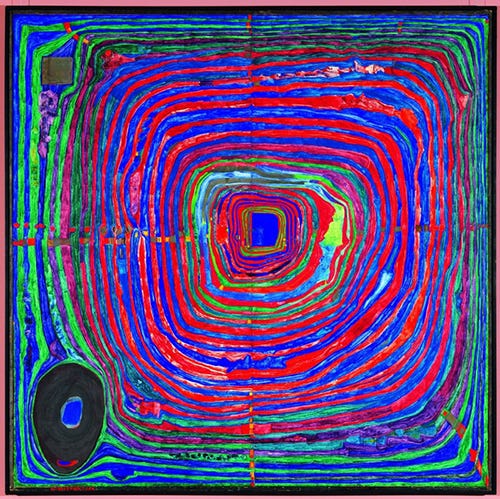

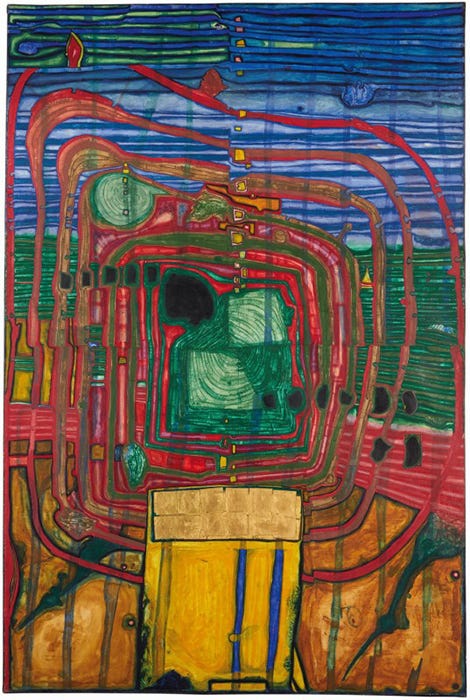

What was it about Hundertwasser’s art that resonated so deeply within me? Firstly, his work possesses an organic quality that merges realism with abstraction, architectural mass with microbial forms, while his use of line, vertical or horizontal is never straight. It all seemed so familiar to me. He had this way of turning my environment upside down and filling it with patterns of primordial configurations. Oddly I’ve been here before, but not in this lifetime.

Hundertwasser christened his painting style “Transautomatism” - the artist’s intent or inspiration is secondary to the viewer’s experience. Hundertwasser celebrates the idea that each person can see something different in a single work of art. There’s no right or wrong way to interpret his creations. This flies in the face of the traditional notion that the artists’ genius defines the creative experience. Perhaps that’s why his work seemed so personal and accessible to me before I began seriously exploring art. For someone caught up in the routine of dry quantitative graduate work, his images were a relief. He conjured an all-abiding natural world in which man-made creations bend with the wind. What a perfect escape from the reality of data collection and mathematical equations that possessed my life and dreams.

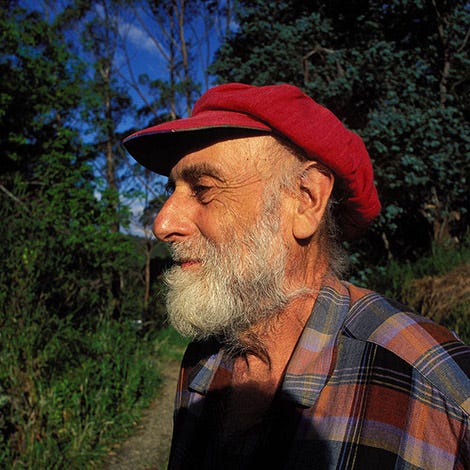

Escape was a theme that dominated Hundertwasser’s early life. He was born Friedrich Stowasser on December 15th 1928, in Vienna, Austria to a Catholic father and Jewish mother. His father died when he was young, but his mother had him baptized in the Catholic Church “for safety’s sake” prior to the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938[i]. Young Friedrich was forced to make the desperate decision to join the Hitler Youth, “as protection for my family.” His membership saved his mother, who, while forced to wear a yellow Star of David, was never apprehended by the Nazis. Unfortunately, other family members were lost to the concentration camps, were not so lucky.

After WWII, Friedrich Stowasser entered the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts where he was introduced to Viennese Modernism and the Secession movement.[ii] After the harsh realities of war, the dreamlike qualities of works by artists like Gustav Klimt, Egon Shiele and Alphonse Mucha created an emotional oasis for the traumatized public. Stowasser gravitated towards Schiele, whose expressive lines embody both beauty and emotional turmoil, a quality also present in Hundertwasser’s work. In 1951 he composed a poetic tribute to Schiele: “I often dream like Schiele, ‘my father,’ about flowers that are red, and birds and flying fish and gardens in velvet and emerald green and human beings who walk, weeping, in red-yellow and ocean-blue.”[iii] He loved the bold colors which Schiele used sparingly, but to great effect in both his drawing and paintings. In Hundertwasser’s hands[iv] similar hues are spread richly across his paintings’ surfaces to transport flowers and gardens, and ourselves as viewers, into a psychedelic realm of deep velvet greens, blues and “red-yellows.”

Delving into Hundertwasser’s work (fortunately, many of his letters and essays have been preserved) I was heartened to discover that he worked intuitively, with little or no planning, let alone professional ambition which he found stifling for himself and artists in general. I share that sentiment as well. “Everything is intuitive” has become my motto. Inspiration is everywhere but you can’t stop to think about it. I’m honored whenever anyone mentions my work in the same sentence as Hundertwasser’s. I couldn’t imitate him if I tried, yet somehow there is a natural affinity.

In his 1990 essay, A Sheep-Like Existence, Hundertwasser wrote with great prescience: “Man must free himself from the greatest and most perfidious serfdom, his dependence on the reduction to the lowest common denominator at the hands of the powerful, which he stupidly - unsuspectingly - accepts, like poisoned candy. OUR REAL ILLITERACY IS NOT THE IGNORANCE TO READ AND WRITE BUT THE INABILITY TO CREATE.”[v]

Hundertwasser didn’t live long enough to witness the ubiquitous mind-numbing distractions of the internet let alone TikTok. But he clearly saw that modern life debilitates creativity, and the powers-that-be like it that way. Without original thought the status quo, as bad as it might be, becomes acceptable.

Having taught studio art as well as art history on the college level, I’ve observed students’ lack of confidence in their own creative potential, as well their ability to interpret a work of art. Hundertwasser’s emphasis on the viewers’ experience as opposed to the artist’s omnipotent genius, helps to empower viewers (especially students) to trust themselves not only to make art, but to develop innovative alternatives to outdated but established norms.

Hundertwasser’s creativity was not limited to the artist’s studio. He was also an accomplished architect and environmental activist. But we’ll save that for another post.

[i] Hundertwasser, Friedensreich. Between Hitler Youth and the Star of David (excerpt). https://hundertwasser.com/en/texts/zwischen_hj_und_judenstern

[ii] In art history secession refers to a historic break between a group of avant-garde artists and conservative European standard-bearers of academic and official art in the late 19th and early 20th century

iii Hundertwasser – Shiele, Archive Exhibitions, Leopold Museum, Masterpieces by Gustave Klimt and Egon Shiele, Vienna 1900 and Art Nouveau. https://www.leopoldmuseum.org/en/exhibitions/114/hundertwasser-schiele

iv Friendrich Stowasser started using the name Friedensreich Hundertwasser while in the studying at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. It translates directly into English as "Peace-Realm Hundred-Water.”

[v] Written 1990 for publication in the Austrian newspaper Arbeiter Zeitung, Vienna (not published). https://hundertwasser.com/en/texts/schafedasein

A beautiful song about Hundertwasser..

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=38Uvl9RUbmo

John Kruth - Hunting for Water

YOUTUBE.COM